The traditional narrative of the British colonisation of India begins with Battle of Plassey in 1757, where the private mercenary armies of the English East India Company defeated the powerful Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daula. For the Companies armies, led by the infamous Robert Clive, the prize of this stunning victory would be the governorship of the immensely wealthy old Mughal province of Bengal. From Bengal, British rule would gradually spread over India, so that they would become unchallenged masters of the continent from the 18th till the very middle of the 20th century.

However, what is less well known that is the rather more ignoble story of the first English attempt at conquest in India, almost seventy years earlier in the year 1690. This is referred to as the ‘Moghul war’ or sometimes the first Anglo Indian war. Unlike Plassey, this resulted in a humiliating and total defeat for the English – so much so that the English would for an entire generation pursue a policy not to engage in land wars on the continent. Indeed, even in 1757 when Clive would annex Bengal and sow the seeds of the British Raj in his infamous ‘200 days’, he would do so against the wishes of his bosses in London.

That the failed escapade of the 1690 Anglo Indian war was usually omitted from Imperial accounts of the history of British India is of course not surprising – the glorious victory at Plassey where a handful of hardy honest English men under Clive defeated a native army which outnumbered them twenty five to one is a much more romantic beginning for the story of the Raj. What is more surprising is that the 1690 victory over the Western Invader scarcely finds mention in Indian nationalist accounts of imperialism, which otherwise are adept in turning even defeats into ‘moral victories’.

The reason for this is the victor of the 1690 war was the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, a pious orthodox Muslim. In India he remains a character of some controversy owing to his break from the tolerant traditions of his more libertine Mughal ancestors when it came to the other religions of India. Posterity has not been kind to him – his zealotry did little to endear him to the more secular minded older generation of post-colonial Indian nationalists , while modern religious Hindu nationalists regard him as practically a demon, the very apex of the Muslim ‘subjugation’ of India.

In today’s right-wing Hindu India where actively forgetting the Islamic roots of our contemporary culture has become a patriotic project, or in today’s bravely post-imperial Britain where people are ‘very sorry’ about the history of colonialism but not very interested, this is unlikely to change. Which is a shame, because it is fascinating story – a tale of incompetence and arrogance to the greater glory of no party and a fascinating look at both the early workings of the East India Company in the days before her empire and at the Mughal empire at the height of her power.

The architect of the first Anglo-Indian war was one Sir John Child, the governor of Bombay and a man in temperament not unlike Clive. Like Clive, so convinced was he about the innate superiority of the Englishman to the pusillanimity and cowardice of the native, that he sought to conquer an Indian kingdom for himself with a tiny mercenary army. However, unlike Clive who was able to take advantage of the power vacuum left by a crumbling and dilapidated Mughal empire , Child would have to face a united Mughal Empire at the very zenith of its power, and in Aurangzeb, a ruthless and powerful adversary.

Part I

Humble Beginnings

The East India Company had humble beginnings in India, for the English were relative latecomers to the game of colonialism. The great colonial powers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were the Spanish, the Portuguese and the Dutch. Indeed, the East India Company itself, which would become ‘the Greatest Company of Merchants in the Universe’ would start out as a very private venture by a handful of private individuals with little support from the Crown.

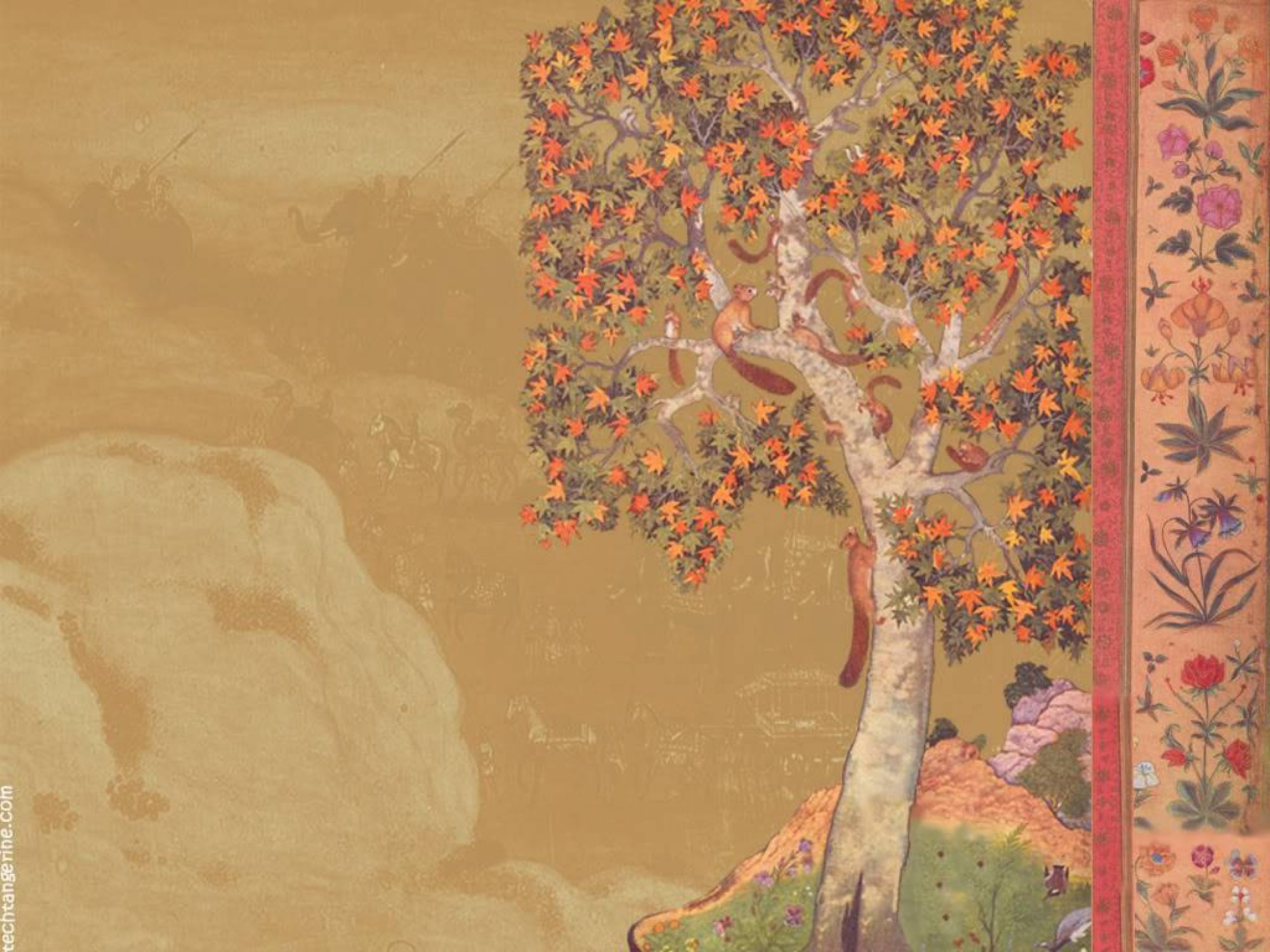

The first formal English ambassador to the Mughal Court was one Sir Thomas Roe. In 1615 Roe landed in India, an aristocratic explorer of the eccentric Elizabethan type. He was a figure of some glamour in England, having charted the then unmapped Amazon and having led three separate expeditions to try and find the legendary city of El Dorado. He now came to India bearing papers announving his embassy on behalf of his king James I to the King of Kings of India, the Emperor Jahangir.

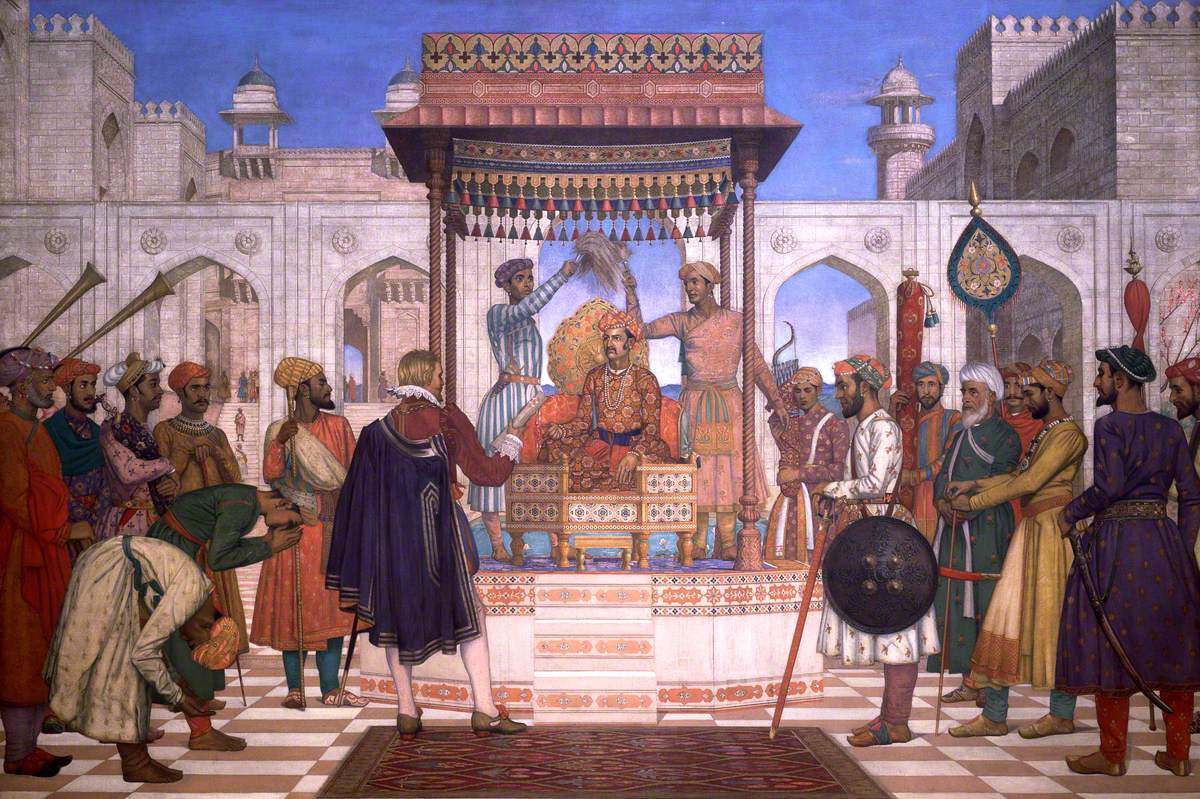

This painting above commemorating Roe in India hangs in the British Parliament. To see it is still to be struck with a strong sense of how difference the power dynamic was in the early days between the English and the Mughal Empire. In Jahangir’s time, the empire was it’s peak and India was in the midst of its last great golden age. Under Jahangir’s father, Akbar the Great, the Mughals had succeeded in uniting much of the northern subcontinent under one ruler for the first time in two millennia. Jahangir was absolute autocrat over 100 million people, almost twenty percent of what was then the worlds population . More people lived in his dominions, he could boast, than in the mighty Ottoman empire, than in all the petty kingdoms of Europe put together. As far as Jahangir was concerned, he was Lord of the whole world – fitting for one who had taken the title Jahangir on his ascension to the throne – ‘World Seizer.’

Roe would soon experience the reality of Jahangir’s indifference to his embassy. He would spend months trying to get an audience with the Emperor, fretting and fuming at the edges of the Court. During this time he and his men were routinely harassed by the Governor of Surat, a man with business links with the Portuguese, England’s rivals. Only after Roe’s fixer in India – a local man who according to Roe called himself ‘Jaadu’, or ‘Magic’- managed to open a line of correspondence between Roe and the Empress Noor Jahan Begum, by many contemporary accounts the true power behind the throne, would this audience come about.

After another four years in India, Roe specifically counselled against the English establishing permanent settlements and a standing army in India ‘Without controversy’ he wrote ‘It is an error to affect garrisons and land wars in India’. He had before him the example of the tottering Portuguese empire, who had indeed maintained forts and conquered provinces in India and had inevitably become drawn into Indian politics, to the ruin of her great empire. The Portuguese’s ‘many rich residencies and territories’, Roe observed ‘have been the beggaring of her trade’.

‘Let this be a rule’, was his advice to the English King’ that if you will to profit [in India], seek at it at sea and in quiet trade’

Thomas Roe, an aristocrat through and through, bore all of the nobility’s disdain for the low-born ‘men of trade’ who made up the then fledgling Company, and had taken a gloomy view of their prospects in India. He blamed the tradesmen in part for his initial failures with Jahangir, saying that the Mughal court had been so awash in money grubbing European adventurers claiming to be the representatives of some or the other European king that the Mughals had been unable to recognise him as a ‘Man of Quality.’ Roe would eventually claim friendship with both Jahangir and the crown prince Khurram (the future Shah Jahan) after finally having had his Quality recognised. It is telling though that Jahangir himself was a keen diarist, and yet his exhaustive memoirs do not mention this friendship at all.

On his own account, when Roe was not enjoying the notoriously hedonistic Jahangir’s wine parties, Roe seems to have spent much of his time undermining the East India Company’s men, criticising many publicly and openly decrying the ‘error of factories’ .

Though later British Imperialists would credit Roe with securing the first ‘trading rights’ for the Company in Surat, keen to establish a long-standing basis for existence of the Company in India, Mughal administrative records show no formal imperial decree, or farman, confirming any permanent grant of land the Company. In any event, the World Seizer did not enter into anything so plebeian as ‘contracts’ – he issued farmans as the Shadow of God on Earth, and any such grant only existed so long as he willed it.

Much to the annoyance of the ambitious East India Company men eager to secure royal backing for their ventures , Roe’s attitude of indifference towards India in general – a ‘dreary place’- and the abilities of the rough, freewheeling Company men in particular remained the dominant view of the English Establishment for the next 80 years. Indeed, matters would get even worse. In the 1640’s and 1650’s, England herself would descend into the Anarchy unleashed by the Civil War between King and Parliament, an anarchy that would only end with the beheading of a King and the estabishment of a short lived Republic, which would proceed to abolish the very Crown that Roe had once represented and from which the Company drew its patronage.

Cut off from their motherland in every possible way, for a time the Company Men in India must have felt truly alone.

Part II

The machinations of Sir John Child, Baronet.

However, by the end of the century, matters would begin to look up from the Company’s point of view. The Monarchy had been restored, and the new king Charles II was a reformer, no doubt by circumstance. Charles’s accommodation with Parliament had meant ceding many of the ancient rights of Kings to Parliament , and as such he was a man much more in touch with the modern world of trade and international commerce.

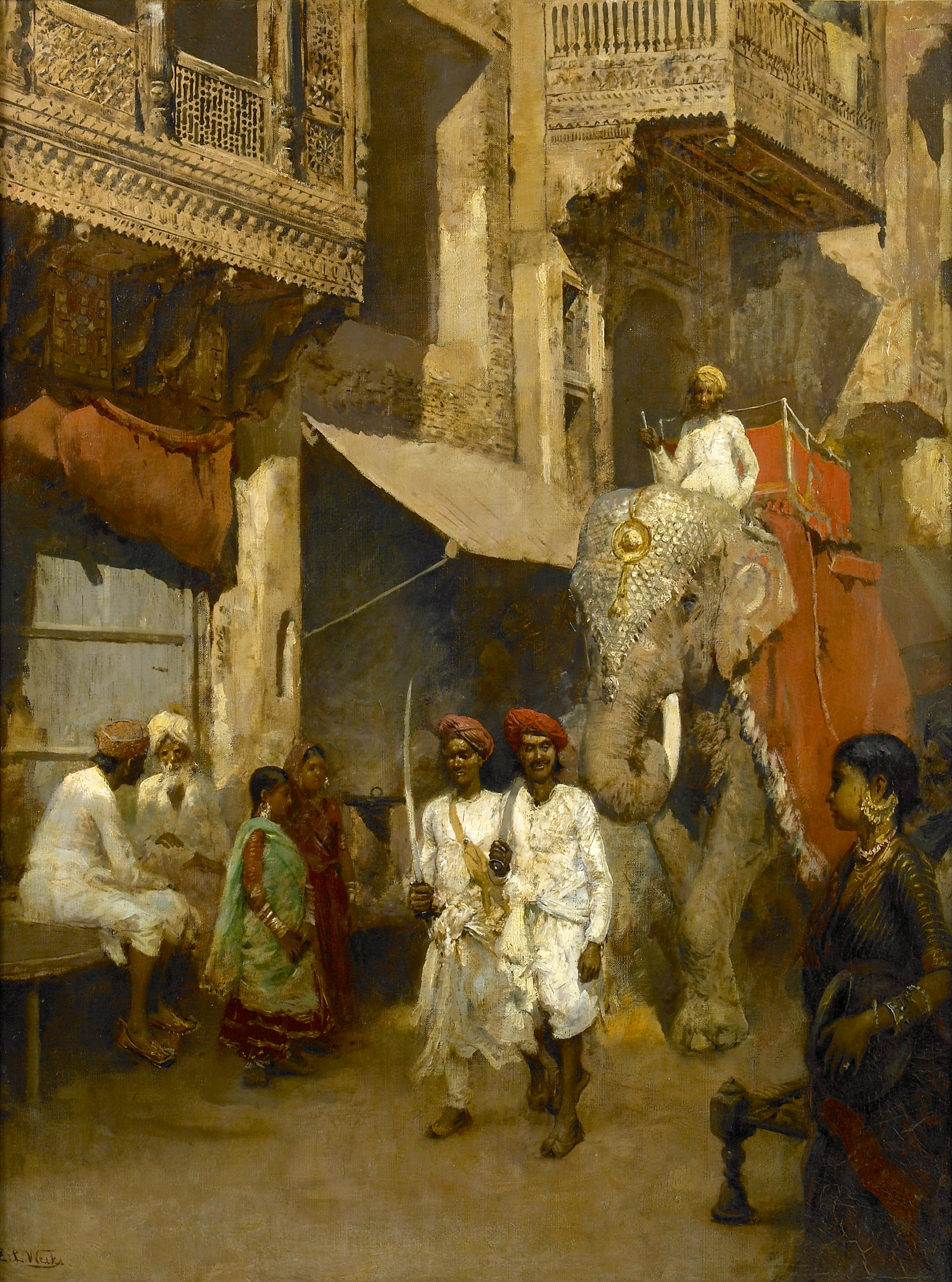

Doubtless conscious of the Company’s many wealthy backers amongst Parliament, Charles II enthusiastically gave his support to company ventures, even leasing the company a small coastal settlement of it’s own on the Indian mainland. Charles II had received the settlement – formerly a Portuguese territory – as a wedding gift from his Portuguese bride. It had turned out however to be an unwelcome expense to maintain- being nothing more than a palm tree laden Portuguese governors mansion and a thin strip of beach on the West Coast of India. The Portuguese had called this tiny unimportant governor’s villa Bon Bahia ‘The Good Bay’ . The English would very soon garble this into ‘Bombay’.

Then, in 1682, a company agent (or a ‘factor’) Sir John Child, who had been in India for three decades in the service of the Company – a man with a wide network of ‘cronies’ and ‘relations’ in India- was promoted to the Presidency of Surat and became governor of Bombay. His appointment was a clear sign that the the time when the Company would determine British policy in India was at hand.

The beginnings of Child’s governorship of Bombay would be inauspicious to say the least. The Board of Directors and shareholders of the Company had long been grumbling about the costs and demands of the ever expanding new settlement. By the 1670s, only thirty years since being leased to the the Company, Bombay had been settled by 300 English, 400 ‘Topazes’ (Indo-Portugese), a militia of about 500 ‘natives’ and about 300 ‘Bhandarees’ – club-weilding toddy tappers who worked the palm trees. Child, a devoted company man and a huge believer in the Company line, would set about a ruthless cost cutting project, slashing Company funding for infrastructure and public works in Bombay. At the same time, he managed to amass a personal fortune of £100,000 and net himself a baronetcy for his service to the Company. Unsurprisingly, these measures were decidedly unpopular with this early generation of ‘Bombay-wallahs’ .

In 1683, one year into Child’s governorship, when Child proposed cuts to the salaries of the English soldiers stationed in Bombay, it was a step too far. Richard Kegwin, a decorated Royalist veteran, raised the standard of revolt on behalf of the free citizens of Bombay, citing John Child’s ‘intolerable exertions, oppressions and unjust impositions’ and accusing him of not ‘maintaining the honour due to His Majesty’. Child was chased out and a Free State of Bombay declared – one of the few instances of an English led rebellion in India against East india Company rule. For the next two years of his Governship, Child would be exiled from his own city, cooling his heels in Surat.

Kegwin ruled this free state of Bombay for these two years and by all accounts his governorship was fair and even-handed, extending to pursuing friendly relationships with the neighbouring Indian kingdoms with a policy of peaceful co-existence and trade. However Charles II had no appetite to step on the Company’s toes, and sent the Navy to relieve Kegwin of his ‘command’ and to return to England. The ‘naughty rascal’ Kegwin finally dealt with, Child could skulk back to Bombay to enact his petty vengeances on anybody who supported Kegwin’s rebellion.

If Child was humbled by this early referendum on his capacities as an administrator, he certainly did not show it. Rejecting decisively Kegwin’s policies of mutual co-existence and casting his eye about the political landscape of India in the closing years of the seventeenth century, he instead saw opportunities for conquest and for the ‘Bombay Presidency’ to become something greater than a solitary outpost at the peripheries of civilized India.

Part III

The machinations of Emperor Aurangzeb

Some eighty years after the death of Jahangir, cracks were finally beginning to show in the once impenetrable Mughal edifice. Jahangir’s grandson Aurangzeb, a deeply orthodox and conservative Muslim, had turned his back on the tolerant traditions of his father and grandfather and had taken the hugely controversial step of imposing jizya, a tax on non-Muslims, throughout his empire. Though jizya was commonplace in most Muslim kingdoms, including the Delhi Sultanate that had preceded the Mughals, it had been abolished by the Emperor Akbar who decreed that none of his subjects would be interfered with on account of their religion. The taint of illegitimacy also hung over Aurangzeb’s kingship, for he had succeeded the throne by imprisoning his father and murdering his elder brother Dara Shukoh, their father’s chosen successor. 1

The Emperor Aurangzeb

Unsurprisingly, Aurangzeb’s reign saw unprecedented religious unrest and Hindu and Sikh revolts throughout his empire, the beginning of the slow but ultimately irreversible unravelling of the Mughal state. Perhaps the most spectacular of these was the rise of the Marathas, Hindu warrior clans from the Deccan hills, who till that time had seemingly been content to be either soldiers for hire in the service of other Indian powers, or free raiders, but out of nowhere had been united by a charismatic and intelligent leader with territorial ambitions of his own, Shivaji of the Bhosle clan.

Shivaji and his followers would proceed to inflict a serious of increasingly audacious defeats on the Mughal empire. The English would experience this first hand when in 1664 the famous Maratha cavalry swept into Surat, the capital of Mughal Gujarat, and plundered the city for forty days without resistance. The English’s main factory in India at the time was in Surat and it would have been looted and burned along with rest of it had not the English factory workers barricaded themselves inside the factory and mounted a surprisingly resolute defence of it from its walls for those forty days. The English were not at this stage allowed to maintain their own army under the terms of farman allowing them to trade in Gujarat and had relied exclusively on the Mughal army for protection, but their ‘protectors’ had instead had been totally outmanoeuvred by the Marathas and cut to pieces. Though the English were pacified by gifts and an exemption of custom tax by the grateful Aurangzeb for their role in the defence of Surat, Shivaji would do an encore performance on the hapless citizens of Surat in six years time and the Board of Directors of the Company would begin to seriously re-evaluate the merits of their continued arrangements with the Mughals.

Mughal control over the sea trading routes was also no longer absolute, for Shivaji, as part of his programme for a modernised Maratha ‘state’ had created the first Maratha navy, and by the 1680s Maratha and Mughal ships were openly clashing near the Bombay harbour itself.Child, referring to these events, was able to persuade the board of the Company, then chaired by a man with whom he coincidentally shared a surname, Sir Josiah Child, that time had come to move away from the long propounded axioms of Sir Thomas Roe not to ‘affect land wars’ in India and adopt instead a stance similar to the long-established practice of the Dutch and the Portuguese in India. That is, they needed permanent residencies fortified by their own armies in which they were ‘soveriegn’ ,so that they were not so dependent on the whims and fancies of ‘petty princes and potentates’

Part IV

Chaos under Heaven

Child’s moment came when a conflict arose between East India Company merchants and the Mughal governor of Bengal over customs duties , which saw a faction of the English agents in Bengal taking arms against the Mughal governor Shaista Khan. Rather than intervening to smooth over the conflict, Child lent his covert support to the rebelling Bengal merchants, encouraging them to secure by force of arms a new permanent settlement in Bengal. The Board, led by his John Child’s benefactor Josiah Child, was persuaded to send a a fleet of warships to aid in this effort – the beginning of Child’s vision of a sovereign English presence in India. Meanwhile Child set about fortifying Bombay.

Somehow Child had expected that all of this would go unnoticed and that the Mughal governor of Surat would keep on allowing them to trade in Bombay as before. In the word’s of one of Child’s critics ‘By what rule of policy could ..Sir John Child think to rob, murder, and destroy the Moguls subjects in one part of his dominions and the Company seek to enforce a free trade in other parts? Or how could he expect that the Mogul would stand neutral?’

Perhaps Child shared the view of Josiah Child, that the Mughals had become so dependent on English trade that they would have to seek terms with the English whatever the cost and be compelled to overlook these power grabs. In any event, this was not to be.

Aurangzeb retaliated by confiscating East India Company shipping vessels at sea and immediately imprisoning all the East India Company agents in Surat, parading them through the streets in chains. Aurangzeb did not have to suffer a loss of European trade either – the East India Company’s trading rights were simply transferred to another European businessman named ‘Messr Boucher’ – a former rival of Child from the days of Kegwin, who had been imprisoned by Child but somehow escaped and sought asylum with Aurangzeb. He had set up a rival company to the East India Company and the Mughals set him up in the recently vacated East India Company warehouses. It made no difference to Aurangzeb, after all, what specific group of Europeans he traded with.

The ‘Bombay Presidency’ of the East India Company was almost brought to ruin by these events. The desperate Child was able to negotiate the release of the East India Company factors in Surat, paying hefty fines to the Mughal governor. When he returned to Bombay however he found out that the Mughals had imprisoned all the Company men in Surat again, almost the moment his back was turned.Child, incensed, ordered retaliatory attacks on Mughal shipping. Warned that his actions would surely attract the attentions of the Mughal Navy, then led by celebrated admiral Yakub Siddiqui, Child replied with his characteristic bravado that he would be able to repel Siddiqui by the force of ‘the air from his bum’.

It was not to be. In 1689, the Mughal Navy, under the command of Yakub Siddiqui himself, landed 20,000 men on the beaches of Bombay. The English were completely taken by surprise. Not a shot was fired from the English side, except the warning gun. The forts of Mazagaon and Mahim were occupied by the Mughals in days and Siddiqui advanced on Bombay castle. Siddiqui then set about erecting artillery batteries, which, according to one of those who later escaped the siege of Bombay ‘bombarded our fort with massy stones’. The English mounted some forays against Siddiqui, but Siddiqui saw them off with ease. The garrison meanwhile was beset by desertions.

As the Mughals occupied Bombay, the hapless English residents had to seek refuge in Bombay castle. In an attempt to starve them out, the Mughals burned the entire city to the ground and the English were trapped in the castle from April to September of 1689, with ever dwindling provisions and sickness soon ravaging their numbers. One Englishman had a brilliant idea to somehow get out a message to appeal for assistance from the Mughals rivals, the Marathas. Though 3000 Maratha cavalrymen did ride to their aid and stave off the Mughal advance for some time, feeding and paying the Marathas for their services further impoverished the hapless English.

Bombay was in the meantime absolutely destroyed by the Mughal army. From a population of about 800 English citizens, there were eventually no more than 60 left alive.

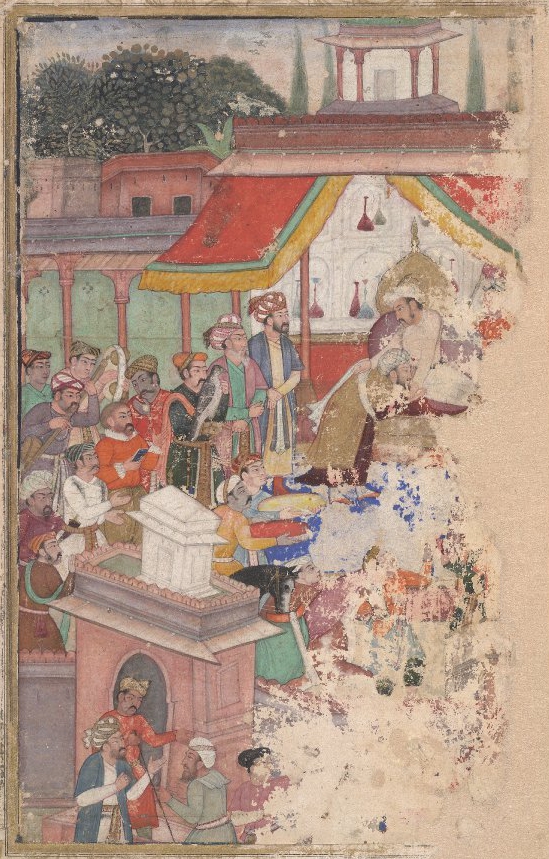

There was nothing else to it. The English had to make peace. The English had to send of their most two senior agents in India to present themselves to Emperor Aurangzeb to try and negotiate a truce. They were immediately imprisoned. With their hands bound in chains, the Englishmen had to perform the abject ritual prostration before Aurangzeb in open court in front of the entirety of the gathered Mughal and Rajput nobility. They were made to go down on their knees and bend before him so that their foreheads touched the ground, begging Aurangzeb’s forgiveness as his ‘errant children’ and as his ‘slaves’.

‘A new mode for ambassadors’ sneered one critic of John Child. Aurangzeb in turn delivered a severe reprimand to the Englishmen, rebuking them in condescending terms. This was not an exchange between two sovereign powers – by doing this the English were pointedly acknowledging the overlordship of Aurangzeb over the English, in accordance with the rituals of Mughal courtly etiquette. It is the exact same ceremony with which a defeated Indian king or rebel would be brought before Aurangzeb and either accept his vassalage or die.

After making them confess their faults and beg his pardon, Aurangzeb relented to restoring the English’s trading rights, but only if they accepted a series of onerous conditions. They had to pay for the repair of all the Mughal ships they had destroyed and compensate the Mughal treasury for all the goods they had plundered. On top of that, the East India Company would have to pay him an indemnity of a 150,000 rupees. Henceforth, Aurangzeb decreed, the activities of the Company ‘must proceed in accordance with my will and according to my pleasure’. Under no circumstances would the English ever be allowed to maintain a standing army in India or militarise as they had tried to do under Child. It went without saying that some Englishmen would have to remain at his court as a guarantee of good behaviour. To quote the historian John Keay, these were the most humiliating conditions the English would ever have to swallow in India.

Aurangzeb was not done. He had one further condition. The English must hand over the detested John Child, to face Aurangzeb’s justice. The English had no choice and duly accepted, imprisoning Child and putting him on a transport to Delhi.

What Aurangzeb would have done to Child was anyone’s guess. While being transported to Aurangzeb’s custody, Child died in mysterious circumstances. ‘A shrewd career move’ one observer remarked acidly.

The story is remarkable because it challenges to the core the traditional imperialist narrative, with glamorous tales of European exploratory prowess and moral and technological dominance over the native. It would by necessity be forgotten in British India because it so undermined the entire basis of the Empire – the inherent superiority of the European to the Native.

However the fact that what may be the most humiliating defeat the English ever suffered at the hands of an Indian king continues to be forgotten in today’s India says as much as about contemporary India. It is as inconceivable to the Hindu nationalist right that the English’s first defeat would come at the hands of the hated Aurzangzeb, as it perhaps was to the Empire that they could be so soundly defeated by a native prince.

In fairness to Child he was perhaps prophetic when he saw the seeds of the Mughal empire’s demise in the policies of Aurangzeb, but the English fatally overplayed their hand by striking out so early. The Mughal empire, though racked by war – Aurangzeb would become an old man in the saddle – remained one of the most powerful empires in the world. In those days, before the industrial revolution and the invention of the Gatling gun and the coming of the railroad, the European enjoyed no inherent technological superiority to the great ‘gunpowder empires’ of Asia like the Mughals, the Ottomans or the Chinese. It would take a few more generations of misrule and a series of catastrophic invasions from Central Asia that would cause the Mughal empire to weaken to the point that Clive could finally conquer Bengal at Plassey.

‘After me, chaos’ Aurangzeb was reported to have said on his deathbed. And so it was.