When I visited Egypt last year, I was assaulted by the sheer weight of time like in no other place I have been before. “Men fear time”, they say, “but time fears the pyramids.” A whopping three thousand years separate the builders of the pyramids at Giza from Cleopatra, the last person who called themselves Pharaoh. Those who know me are probably bored of hearing me say things like Cleopatra is closer in time to the invention of the iPhone than to the builders of the great pyramid of Khufu. I felt moved to write something about it all…but how to convey anything about a period of time a thousand years longer than the Roman empire to today?

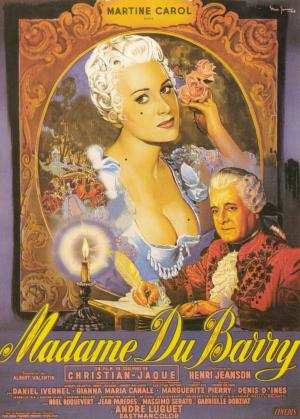

So I’ve decided to focus on one of my favourite episodes in Egyptian history – the unlikely rise of Egypt’s greatest dynasty – the eighteenth – and the story of one of that dynasties most formidable rulers – the woman Pharaoh Hatshepsut.

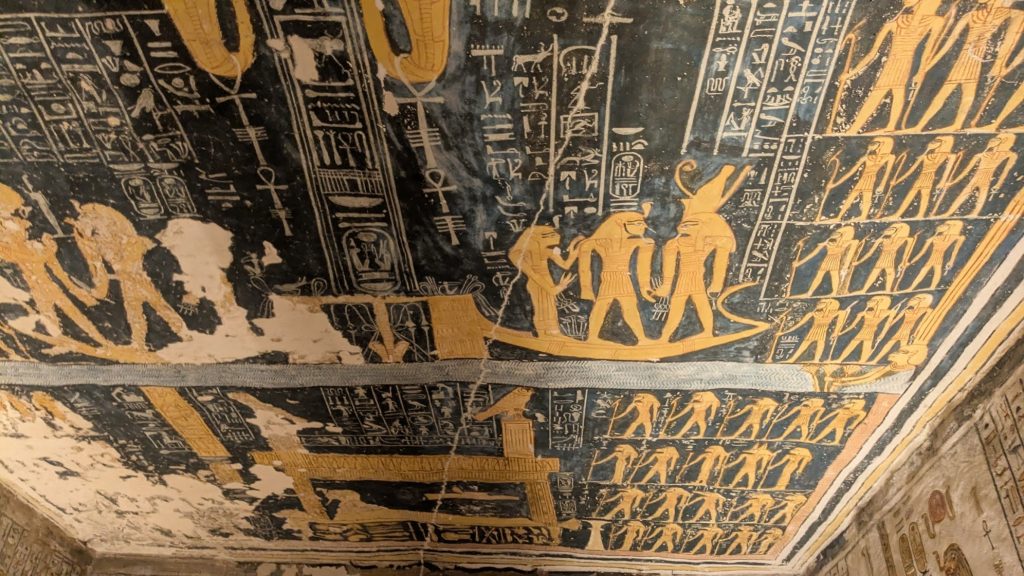

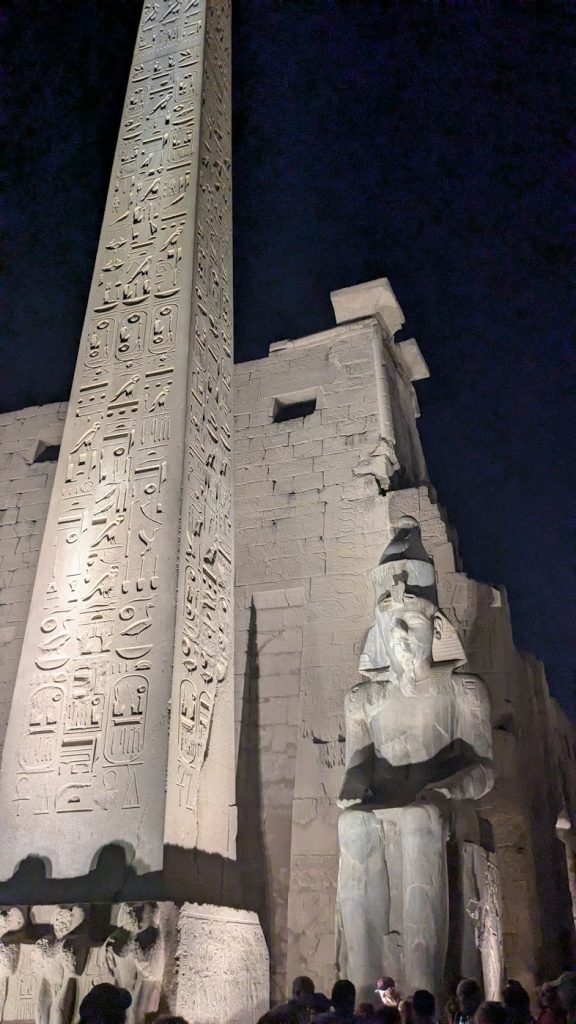

This 18th dynasty comes almost a thousand years after the pyramid builders of Giza (as remote to them as the Vikings are to us). It is the monuments of these kings in their capital of Thebes (modern day Luxor) which are arguably the most breathtaking sites in all of the country to visit, in my opinion, surpassing even the Pyramids.. If you are familiar with any myths and legends of ancient Egypt, this is when they took their final form.

Yet this golden age was far from given. This is because just before this family came to power, Egypt experienced a cataclysmic event which nearly saw their civilization extinguished, destined to be forgotten in the way of so many obscure bronze age civilizations..

Conquest and rebellion

A hundred years before the birth of the Eighteenth dynasty, an Eastern Mediterranean peoples known as the Hyksos comprehensively ended the fourteenth dynasty of Egyptian kings, decimating them with two brand new technological innovations previously unknown in Egypt- horses and chariots. They established their capital in Huwaret in Northern Egypt, near the Egyptian’s ancient capital of Memphis, in the shadow of the Pyramids.In Huwaret, they built great temples to their God Baal Zephon, and an enormous citadel over half a million square metres of reclaimed land.. Enriched by the trade of olive oil, wine and timber from Cyprus and Palestine, the Hyksos cemented their rule over the northern half of the country, building fortresses to signal their military might to the population. Through either bribery or subjugation, they were eventually able to persuade all of the northern Egyptian lords to accept their overlordship.

Taking advantage of the situation, the Egyptian kingdom’s former vassals in the Nubian kingdom of Kush – which straddled what would have been contemporary southern Egypt and northern Sudan – decided to make war on their former overlords. They pushed upwards, routing the demoralised and underpaid Egyptian soldiers without much of fight, and raided the southern half of the Egypt, occupying the very same border forts once built by the Egyptians to keep them out.

So it was that the Egyptians found their ancient kingdom drastically reduced to the area around Thebes, in the middle of the country. Outwardly, the lords of Thebes maintained friendly relations with the Hyksos Kings. Privately, they dreamed of a day when they would retake their ancient lands in the north.

The push back began modestly, with a king of Thebes called Rahotep, who began a programme of restoring shrines around Thebes destroyed by the Hyksos, restoring the cult of the local God of the Dead, Osiris, at Abju. His successors continued these programmes of restoring ancient monuments, eventually building – for the first time in centuries – rudimentary pyramids. These mud brick pyramids were modest affairs compared to the great stone pyramids of old, but signalled to the world that the old ways endured under Theban rule. Slowly but surely, the Thebans kings began arming their subjects for war. Matters progressed until one of the kings of Thebes finally began drawing up a battle-plan for an all out assault on Huwaret. Unfortunately, the King of Kush chose this moment to send a great army against Thebes, forcing the Thebans to rush back home, only barely preventing the Nubians from sacking their home city.

The fortunes of Thebes seemingly changed with the accession of a king called Seqenra Taa. Taa was every bit the swaggering hero, whose brashfulness was matched by an instinctive understanding of military strategy After leading several successful raids against the Hyksos, he publicly challenged the Hyksos King Apepi for the ancient crown of the Two Lands.

One of the reasons why the Hyksos remained unpopular was because they refused to recognise the old Egyptian Gods, preferring to worship Baal Zephon, their ancestral god. The Hyksos king Apepi, perhaps spooked by the popularity of this new Theban king amongst his Egyptian subjects, broke with this tradition.

Apepi declared himself a follower of the Egyptian God Set, who, like, the god of his fathers Baal Zephon, was a storm god. Set was also, fittingly, the God of strangers and foreigners. Given Taa’s association with the Theban god Osiris,, lord of the underworld and mortal enemy of Set, the stage was set for a cosmic rivalry.

.Taa made the first move, capturing from the Hyksos a large hill called Dier el-Ballas, on the West bank of the Nile. The high hill, which overlooked the old capital of Memphis and Huwaret itself, was a perfect defensive location, and Taa built a great fortress there, and supplied it with a large bakery, so that it could withstand years of siege. From this fortified command centre, Taa launched a series of raids against Apepi. Utterly convinced in his destiny, Taa led these raids from the front – contemporary sources describe him riding joyfully into battle in his chariot, a large man with an enrormous muscular frame and thick black hair This machismo would prove his undoing – less than four years after ascending the throne, Sequenra Taa would be pulled from his chariot by some of Apepi’s men and captured during a minor raid. Sentenced to ritual torture and execution, Taa would be be cheated of his glorious destiny by having his head caved in by a Hyksos axe.

With Taa died the hope of the stunned Thebans, so close to their dream of restoration of the Egyptian empire. Now all their hopes fell on Taa’s inexperienced son Kamose and his formidable widow Ahotep. Ahotep, it should be said, was also Taa’s sister. The Theban royal families practised the ritual incest which would come to define the later generations of Pharoahs, with every generation of Kings marrying their sons to their daughters to protect the ‘divine’ blood line. There is an obvious practical dimension to this arrangement in terms of limiting claimants to the throne, but the religious dimension was to affirm the divinity of the royal families by having them imitate the brother sister marriages of the Gods, like Isis and Osiris.

In any event, Ahotep and Taa seemed to have a genuine affection for each other – she took up residence in her brother’s fortress at Dier el Ballas and Taa was said to have sought out his sister’s counsel before every battle. With Taa’s passing, she became advisor to their son Kamose.

Kamose the Avenger

When Kamose and Ahotep recieved the mutilated body of Seqenra Taa to administer his funeral rites, the boy is said to have been overcome by the enormity of the task before him. It fell to his mother, the grieving widow Ahotep, to take up the reigns of the state juggling, not just her bereft son, but the frightened nobles who kept threatening to go over to Apepi, and the intrigues of Thebes ambitious, suddenly masterless generals. An inscription to her on her memorial reads.

“Ahotep is the one who has accomplished the rites, has united its officer class; and she has protected it; she has returned its deserters and she gathers its dissidents; she has pacified Upper Egypt and she quells its rebels, the King’s Wife, Ahhotep, living.”

When Kamose finally felt himself able to call his first great council he was urged by his leading nobles to seek peace with Apepi. It was not an unreasonable request – the Hyksos were terrible in battle but not especially oppressive overlords – the Egyptians who had accepted their rule seemed to be prospering, and they had been content to leave the Thebans to their own devices before Kamose’s father and grandfather had started making trouble.

However, Kamose, for better or worse , ultimately resolved to continue his fathers war. How could he call himself lord of the two lands when Apepi ruled Lower Egypt? It also must have galled him to make peace with his father’s killer. “I will grapple with him.” He announced his decision on a commemorative stele which still stands today “I will rip open his belly. I will rescue Egypt”

He had the Queen Mother Ahotep’s full backing in his. Kamose first moved to deal with his problem in the south – sending a loyal courtier Teti to reconquer the frontier fortresses south of Aswan that had been lost to the Kushites. Teti succeeded and was awarded the title ‘First Son’ of Egypt – entrusted to rule the southern borders of Egypt as viceroy, reporting only to Kamose himself. Kamose no longer had to worry about a surprise attack from his rear by the Kushites.

Kamose then threw down the gauntlet to his man who had slain his father – Apepi. His first target was the Egyptian lords in the north who had accepted Hyksos rule . To send a message to any “collaborators”, Kamose picked three towns whose Egyptian lords had allied themselves with the Hyksos, invaded them and burned them to the ground.

By a stroke of luck, Kamose’s spies captured a Hyksos messenger on the desert trade route between Huwaret and the Kushite kingdom. The contents of the message could not have been more explosive – it was a message from Apepi himself to the King of Kush

From the hand of the ruler of Hutwaret. Aauserra, the son of Ra Apepi, greets the son of the Ruler of Kush. …Have you noticed what Egypt has done against me? The ruler who is there, Kamose . . . penetrates my territory even though I have not attacked him as he has you. He chooses these two lands in order to afflict them, my land and yours, and he has ravaged them. Come northward, do not flinch. Look, he is here in my grasp. … I will not give him passage until you arrive. Then we shall divide up the towns of Egypt

Here it was – proof of a plan between the two great enemies of Thebes to join forces and annihilate what remained of Egypt. There could no co-existence with Apepi. All of Thebes had to support Kamoses, or all of Thebes would perish. Kamose ordered his men to release the Hyksos messenger, and send him back to Apepi with a simple but chilling message of his own.

“I will never leave you alone; I will not let you walk upon this earth, anywhere you go, I shall bear down upon you.

Not only had Kamose seen off a potentially devastating alliance between his enemies, he knew now that Apepi was not confident that he would win any battle the Thebans took to him without outside help. So Kamose marched north. His army reached all the way to the outskirts of the Hyksos capital Huwaret. By the end of the year his men, Kamose sent a further boasting message to Apepi from Apepi’s own personal vinyards.

I drink of the wine of your vineyards which your men whom I captured pressed out for me. I have smashed up your resthouse, I have cut down your trees, I have forced your women into ships’ holds , I have seized [your] horses; I haven’t left a plank to the hundreds of ships of fresh cedar which were filled with gold, lapis, silver, turquoise, bronze axes without number, over and above the moringa-oil, incense, fat, honey, willow, box-wood, sticks and all their fine woods

Kamose would ride his horse within sight of great palm tree covered citadel of Huwaret itself, which he contempuusly called ‘The House of Brave Words’’, daring the king to come leave it’s thick falls and face him. The women of Apepi’s household peering through their windows at him were like so many baby mice, he joked.

Yet, for all of Kamose’s jokes Apepi’s citadel did not fall,. Kamose eventually was forced to lift his siege and return to Thebes, denied a knockout blow against his enemy/. It could be imagined that the vast caravans of Hyksos wealth he carried back with him offered some comfort.

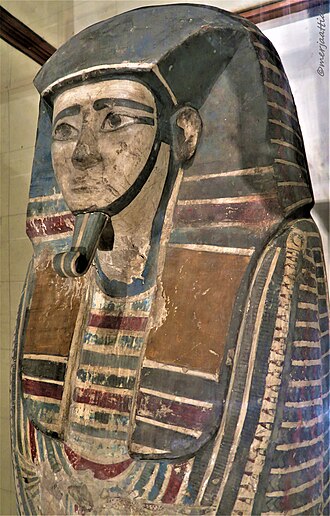

Yet, for a second time,, tragedy at the moment of the Thebans greatest triumph. A mere months after Kamose great victory over the Hyksos, all of Egypt would be greeted by the sight of the young king in his funeral shroud, ready to join his father Taa in the Afterlife. The hasty nature of his burial suggests death was unexpected, but whether it was by poison or Hyksos assassin or simply any of the countless diseases that could strike the healthiest man down in the Bronze Age in the prime of his life, will forever be unknown. Unlike Taa, his mummy is lost to us.

Of course, there was much rejoicing in the halls of Huwaret. Apepi had survived the father, now he had survived the son. The heir apparent to Kamose -his little brother Ahmose, was a child of six or seven, a good ten years away from being able to ascend the throne of Thebes. Thebes leadership was sure to be in chaos. It would be an easy matter for Apepi to gather his forces and eliminate that troublesome city once and for all.

Her name is Ahotep, and the coming of Ahmose

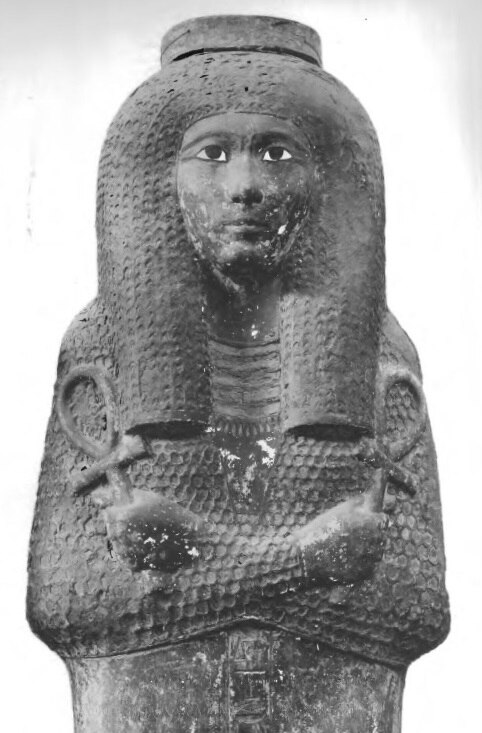

Yet Apepi had not reckoned with the strength of the indomitable Queen Mother Ahotep, who once again ascended the throne of Thebes, this time as mother-regent to the baby Ahmose. Mother to one dead national hero, wife to another, she was now a figure of religious awe to the Egyptian resistance. Her de-facto reign in her son’s name would last a full ten years – longer than Taa’s and Kamose’s combined. Ahotep singlehandedly saw off threats from both the Hyksos and the Kush during this decade of total war. Uniquely for a queen, her tomb is full of weapons, and a necklace with three fly-shaped pendants – the highest military honour in Egypt. Many theorise that this shows that Ahotep was a literal warrior queen, leading from the front in a chariot like her old brother husband Taa, well into her late 40s and 50s.

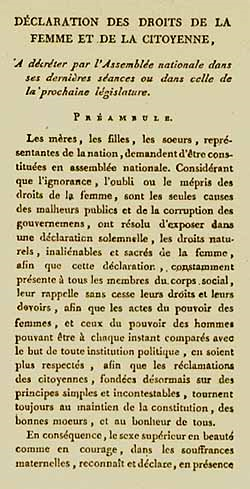

Ahotep would set the precedent for the unusually powerful women of the 18th dynasty – which would find its greatest expression in the woman king Hatspeshput. When her son Ahmose came of age, she would marry him off to his sister, her daughter Ahmose Nefretari. Ahotep was likely behind the prince Ahmose’s genius idea to decree that henceforth, the king’s wife would also be the ‘God Wife of Amun’. Amun, a sky god and Thebe’s most important deity, had displaced the sun god Ra as the most important god of Egypt in these years of Thebes ascendancy as the last free city of Egypt . Ra himself would become a mere aspect of Amun – who would henceforth be worshipped as Amun-Ra.

The position of God’s wife of Amun, created for Ahmose Nefretari but henceforth reserved for every queen, in effect made the king’s wife co-head of the priesthood of Amun. Not only did this irrevocably intertwine the destinies of the royal family and Egypt’s most important priesthood, it ensured that henceforth the queens of Egypt would wield enormous political power, almost on par with the King. This was the equivalent of a European monarch decreeing that the king’s wife would also be the Pope.

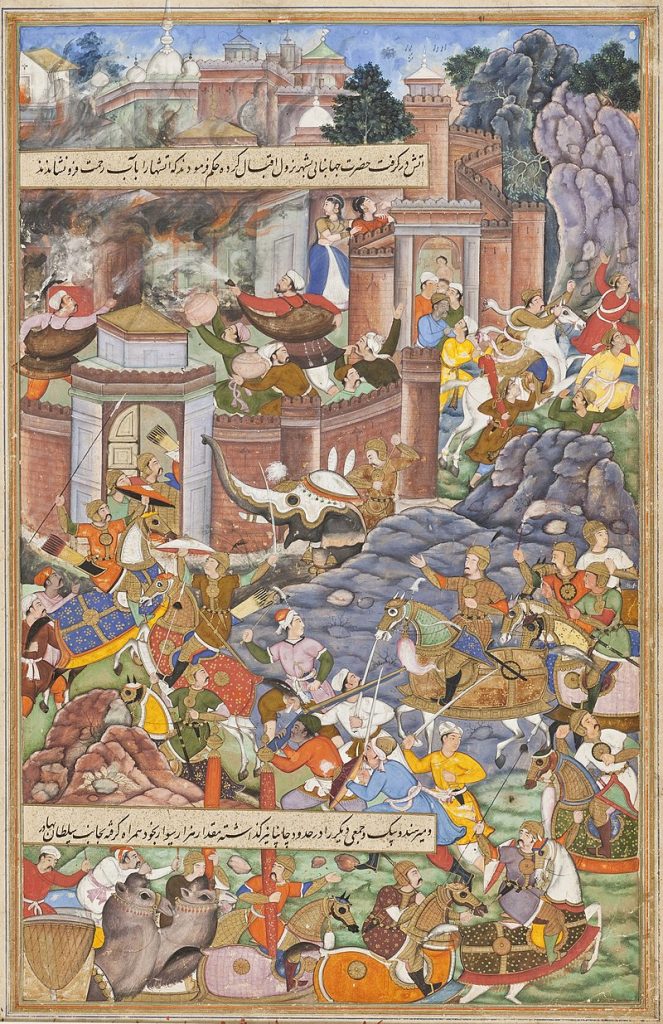

With the God Amun now firmly in his corner, Ahmose would set out to finish the great work of his father and elder brother. Luckily for us, we have a first hand account of the war from one of his generals, a man also confusingly called Ahmose, of Abana. Ahmose of Abana led a flotilla of ships up the Nile to blockade Huwaret, while Ahmose the King laid siege to it by land. Apepi mounted a stiff resistance for years, but ultimately, Ahmose was victorious. Apepi was spared witnessing the death of his house, dying a year before Huwaret was taken. Ahmose of Abana records that Huwaret was plundered abd utterly destroyed. The Hyksos fled Egypt for their fortresses in what is now Syria and Palestine, but Ahmose would not rest until the Hyksos threat was eliminated forever. For three years, Ahmose remained in Palestine, overseeing the complete destruction of the Hyksos. In the end, they were completely wiped out, and Egypt found itself in possession of an empire which reached all the way to Syria and Palestine.

Victorious, Ahmose ordered the construction of the greatest temple Egypt had witnessed in ages – a temple to his mother Ahotep in Karnak, venerated as the true liberator of Egypt. Ahmose had not only retaken the lost lands of his ancestors, but extended them far beyond its traditional borders.

Ahmose was succeeded by his son Amehotep. Amenhotep, guided by his powerful mother and God wife of Amun Ahmose Nefretari, would eschew war in favour of building of great temples throughout the land, particularly at Karnak, It was Ahmenhotep who began the tradition of burying royals in the valley of the kings, and it is he who we have to thank for founding Egypt’s most famous tourist trap. Yet, despite being the first king of Egypt who could be legitimately claim the ancient title of lord of the two lands for more than a century, a shadow hung over his reign. Ahmenhotep was sterile, almost certainly the result of inbreeding- he was after all the product of three generations of brother sister marriages. Fortunately, Ahmenhotep had the foresight, in the last year of his reign, to adopt his brother in law, a brilliant general known as Thutmose, as his heir.

Glory

It was an inspired choice. From the time of Kamose onwards, Egypt had seen a succession of child kings. Thutmose was the opposite – a 46 year old man when he ascended the throne,, a grizzled veteran of the wars against the Hyksos, and a brilliant general. It is Thutmose who is credited as being the founder of the Egyptian empire. The kings of old had been content to keep to the traditional borders of Egypt. Thutmose’s experiences of Hyksos domination however convinced him that for Egypt to be truly safe, it would have to control the lands around it so no peoples like the Hyksos could even dream of threatening them again. The former Hyksos possessions in Syria and Palestine were now theirs, but there remained powers as great as them in the land.

One of Thutmose’s first targets was the Nubian kingdom of Kush. Kush had been a constant thorn in Thebes side during the war of liberation against the Hyksos, often choosing the most inopportune times during that conflict to launch massive raids into Theban territory. Before that, the Nubian kings had dared to claim the south of Egypt for themselves , an insult keenly felt in the century of humiliation preceding Taa’s rebellion.

Ahmose had already led several campaigns into Kush after defeating Apepi – claiming for Egypt their gold mines, the main source of their wealth. Thutmose resolved to destroy the weakened Kush once and for all, thereby both eliminating a future threat and making a statement to the world that Egypt had returned.

So Thutmose marched on the Kushite capital of Kerma, and began a terrifying onslaught of the Nubian city with his army, surprising them at the same time with a river attack,- employing that classic strategy of having his men carry his boats overland. Every Nubian male above the age of twelve was designated an enemy combatant and slaughtered. Thutmose desecrated the Kushite temple and burned Kerma to the ground. Thutmose then carved a victory poem into the rocks surrounding the city, brutal even by the standards of his time.

There is not a single one of them left.The Nubian bowmen have fallen to the slaughter,and are laid low throughout their lands.Their entrails drench their valleys. Gore from their mouths pours down in torrents. Carrion-eaters swarm down upon them.

Thutmose left several such inscriptions throughout the lands of Kush, one of them boasting that he had travlled to the ends of the earth and not found a enemy who could stand up to him. One of these inscriptions stands out, but attests to the presence of his favourite child with him on his campaign- not his heir Thutmose II, as may be expected, but his beloved daughter, Hatseshput, who for the first time bursts into the light of history.

Thutmose ended his genocidal war against the Kushites by having the Kushite king strapped alive to the prow of his flagship, the Falcon. He would sail home months later with the flayed, wind eaten royal corpse still on display, a warning to any who would even think about lifting their hands against Egypt.

Thutmose then turned his attentions north, to a peoples called the Mittani. An Indo-Aryan horse tribe, they were related to the tribes who settled north India, probably worshipping the same Vedic Gods. The Mittani had conquered the ancient kingdom of the Hittites in Mesopotamia. Ordinarily, this would be too remote to be of concern to the Egyptians, but Thutmose saw in these Mittani a new possible threat to Egypt. So he marched north against the Mittani in Mesopotamia, lands farther north than any Egyptian king had ever been. True to his style, Thutmose had an inscription marked on the banks of the Euphrates celebrating himself, marking the greatest extent of the Egyptian empire.

These victories earned Thutmose the notice of that elite club of God-Emperors of the Near East – Babylon, Assyria and the Hittites, who all sent embassies to the court of Thutmose acknowledging him as a brother. When Thutmose died, he would leave behind an empire that stretched from Syria to Sub-Saharan Africa.

Queen, King, God – Hatsepshut’s rise

Bound by tradition, Thutmose name as heir his son Thutmose II, though not before marrying him to his half-sister Hatshepsut. Yet, Hatshepsut was Thutmose’s favoured child – and as daughter of Thutmose’s primary wife, Hatshepsut would be justified in feeling that she had greater right to the throne than her husband,a mere secondary consort’s son. After her husband’s death after only three years of ruling, Hatshepsut would ascend the throne of two lands as queen regent to her infant stepson Thutmose III, her husband’s son by a concubine.

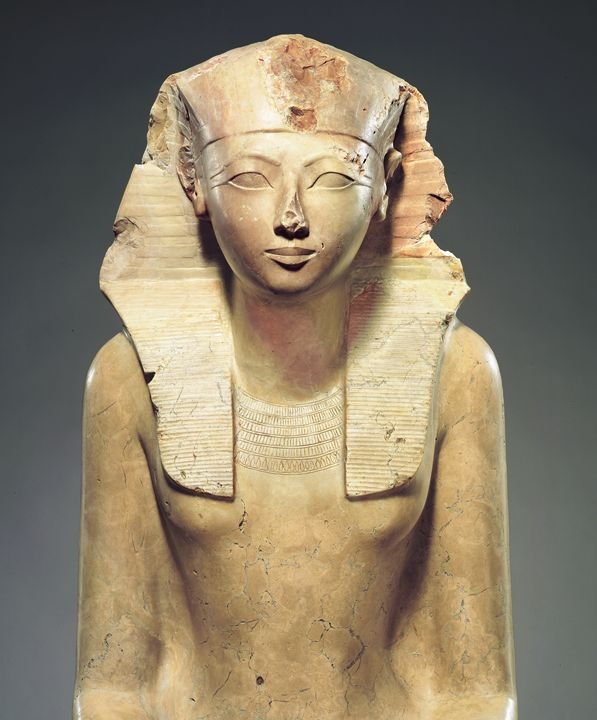

So for, nothing unusual – powerful queen regents and high priestesses who were rulers in all but name had been common enough in the 18th dynasty since the time of Ahotep., Hatshepsut was however every bit her father’s daughter, and would not be content with ruling in “all but name”. So, after this initial settling in period, Hatshepsut went for broke – adopting a royal cartouche and the full paraphernalia and ancient titles of the Kings of Egypt, declaring that she was no longer merely regent for the boy Thutmose III, but his senior co-king.

Hatestshput had diligently laid the groundwork for this unorthodox ascension. She was already God Wife of Amun, and had proved popular amongst her priesthood. Thanks to sitting on three generations of plunder from the Hyksos and Kushite wars, she also had deep pockets. She was able to finance a close friend in his campaign to become High Priest of Amun, her co-head of the priesthood. She was also able to make herself patron of the legendary architect Ineni, who had built monuments for Thutmose and Ahmenhotep.. With temple building and royal monuments once again on the rise following the end of Hyksos rule,, great builders once again commanded considerable influence and prestige and this was a considerable win for the young queen.. Finally, she married her ward Thutmose III to the granddaughter of the quasi-mythical war veteran Ahmose of Abana – that old companion of King Ahmose in his war against Apepi, who was still somehow kicking around. This ensured the army’s loyalty. Having ensured that all the most important political positions in Egypt were occupied by friends and allies, no one mouthed any opposition when she took the provocative step of dispensing with the charade and naming herself King.

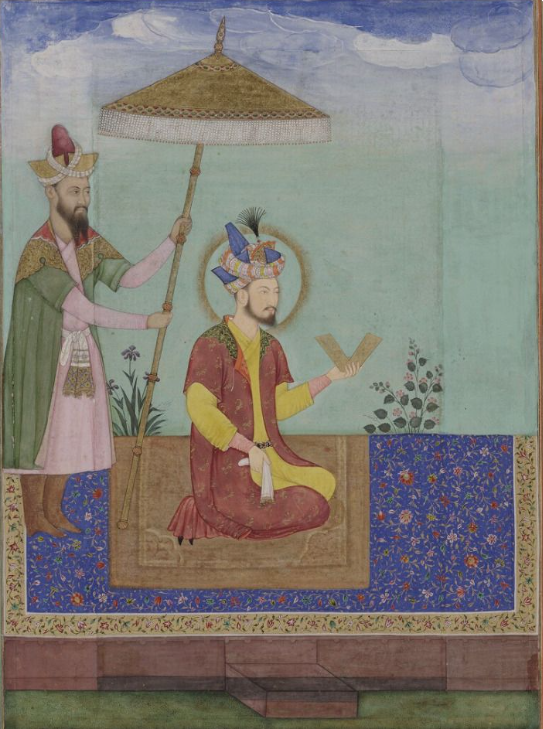

Beyond the patriarchal prejudices of the time, Hatshepsut’s ascension presented a religious problem – for according to the Egyptian religion every king was a manifestation of the God Ra – amongst whose many characteristics was being the supreme male deity. A female king was therefore a theocratic impossibility- there was no word in ancient Egyptian for queen. Such was Hatshepsut’s popularity that not only did the priesthood not object to her adopting royal titles, they obliged her by inventing a gender neutral term to address her. The word per-aa, means great house and was traditionally used to denote the king’s household – this would now be Hatshepsut’s title and the tile of her successors. So it was that Hastsepshut would be the first person to bear the title Per-aa, or as we know it now, Pharoah.

Hatsepshut would demand more of her priesthood. She may have the priesthood’s loyalty now, but her womanhood was not her only vulnerability. Thutmose, after all, was not the blood descendant of Ahmenhotep. So, she had the priesthood of Amun-Ra formally declare that her true father was not Thutmose, but the God Amun-Ra himself. Inscriptions in her new temples declared that Amun-Ra, taking the form of Thutmose, had seduced Hatshepsut’s mother. The Queen mother had awoken from the fragrance of the God, and before the moment of conception, Amun-Ra had revealed himself to her in his divine form, and the Queen is said to have cried out with joy .

The product of that divine union was, of course, Hatshepsut. The God had spoken to her and revealed her sacred lineage, the priests said. Welcome my sweet daughter, my favourite, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare, Hatshepsut. Thou art the king, taking possession of the Two Lands

Not that Hatshepsut neglected the memory of her earthly father, the great conqueror Thutmose. Slowly, but surely, however, the name of her short-lived husband Thutmose II disappeared from royal inscriptions, and it increasingly seemed to all that the crown had passed directly from Thutmose to his daughter.

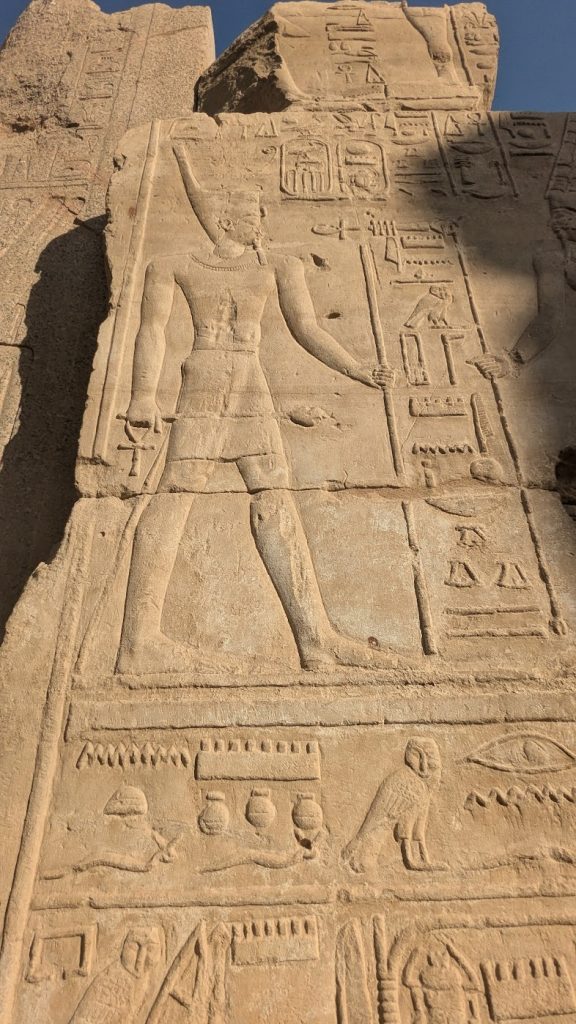

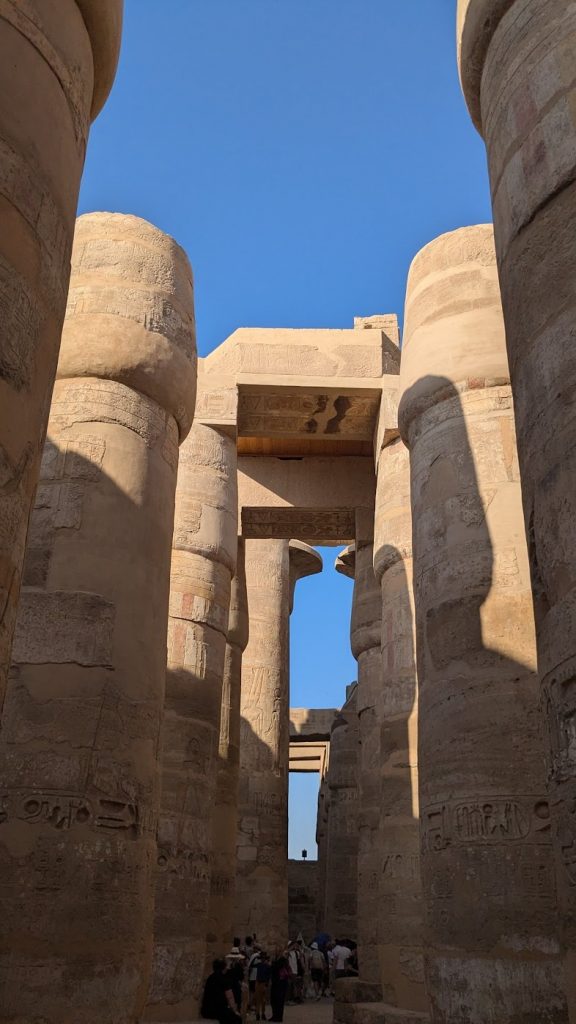

Hatsepshut was every bit as ambitious as her father, though her view was that to truly make Egypt a great power it would have to do more than simply conquer its neighbours, it would have to capture their imaginations. If Thutmose had extended the empire’s military reach, Hatsepshut resolved to extend its cultural influence to greater heights than it had ever been before. She embarked on the greatest programme of monument building since the time of the Great Pyramids -overseeing the construction of literally hundreds of temples, obelisks and shrines throughout Upper and Lower Egypt. Many of these were entirely experimental designs from the mind of the prodigy Ineni – from rock cut shrines on the heights of Sinia to a stone temples deep in Nubia. The greatest beneficiary of this investment in culture was the city of Thebes, which would come to be known to ancient travellers as the ‘city of a thousand gates’. She began by vastly expanding the then modest temple complex of her old priesthood of Amun-Ra at Karnak, transforming it into the preeminent national shrine in the country. She built the first of its famous pillared halls. At the core of the temple she rebuilt the sanctuary, and Ineni designed for her a vast new gateway, the largest ever at the time. This was fronted by six colossal statues of the female king. Nearby, she also erected the famous chapel rogue from blocks of red sandstone and black granite. She is remembered most today for her mortuary temple, a massive edifice cut into the side of a cliff at Deir le Behari, still regarded as one of the crowning achievements of Egyptian architecture.

I was able to visit the massive obelisks she built at Karnak dedicated to Amun-Ra, her divine father. Her inscriptions in these speak of a confident and self assured ruler.

I have done this with a loving heart for my father Amun . . . I call to attention the people who shall live in the future, who shall consider this monument. . .My heart directed me to make for him two obelisks of electrum [a natural alloy of gold and silver], their pinnacles touching the heavens . . .Now my mind turned this way and that, anticipating the words of the people who shall see my monument in future years and speak of what I have done

Hatshesput also is responsible for the expansion of the temple of Luxor and building the avenue of sphinxes, a road lined with hundreds of sphinxes bearing her face, as well as restoring the ancient precinct of Mut (which was also currently being restored when I went, unfortunately).

Karnak and the temple of Luxor would be added on to by her descendants, and today, most of the best preserved parts of Karnak and Luxor – and thereby the most snapshot worthy – are either additions by her descendant Ahmenhotep III or the nineteenth dynasty’s Rameses II. However, these kings were simply building upon the groundwork that Hatshepsut had laid for them. It was around now that Egpyptian culture entered into the form we know it today,

Her greatest cultural contribution would be the festival of Opet, which would become the most significant religious occasion in Egypt all the way to the time of Cleopatra. This would be a yearly festival where the icons of the gods Amun, Mut, and Khonsu would be taken from their sanctuaries in Karnak, and paraded down the avenue of a hundred sphinxes to Luxor. The vast throngs of crowds which would gather to see the statues would be a familiar sight to those used to the parading of the saints in Catholic countries during feasts. It marked a shift in the Egyptian religion, from private cults centred around the person of the king, or temples to which only the very rich could travel and gain access, to increasingly public spectacles designed to bring the monarch closer to the common people. Though Opet may have originated with Hatsephut’s desire to cultivate as many sources of legitimacy as possible, it is impossible to understate how important this festival would become .The equivalent would be inventing Christmas.

Her 22 year reign was one of peace and prosperity, with no real challenges to her rule – though her patronage of one particular man of ordinary birth, Sennemut, whom she promoted to the most powerful offices in the land, and even depicted on her monuments, did spark scandalous rumours of a most un-Godlike dalliance with a commoner.. The real opposition would come only after her death, potentially beginning with her perennially sidelined stepson Thutmose III who finally ascended to the throne and set about striking his stepmother’s name off royal inscriptions – though there is debate in Thutmose’s case whether this was an act of vengeance or mere political necessity after so many years in the shadows.. Thutmose III’s 33 year long reign would see a resumption of the martial exploits of his namesake, and he is now referred to as the ‘Egyptian Napoleon’ due to his reputation of being undefeated in battle, extending the borders of Egypt to its greatest geographical extent. (An irate Egyptian tour guide told me once that by all rights Napoleon should have been called the French Thutmose, given that he preceded the general by millenia and Napoleon famously could not boast a similarly undefeated record after Waterloo.) The exploits of Thutmose III would take up another blog of this size, so I will not digress!

Suffice to say, even if Hatshepsut’s name would be tarnished following her death, her memory endured. Her dynasty would reign a total of 250 years as absolute masters of Egypt. Though she did not witness the true height of the 18th dynasty – this would arguably be the reign of one of her successors, Ahmenhotep III – the achievements of her successors were all built on a cultural foundation laid by her.

Of course, nothing lasts forever, and after this quarter of a millennium, the eighteenth dynasty would be brought crashing down in a fashion every bit as dramatic as its rise under Taa, Kamose and Ahmose. The catalyst would be the single reign of an insane Pharaoh with delusions of godhood unsavoury even by the standards of the autocratic dictators of the time . That however must be a story for another time.